Talking Machines

Whose voice would you most like to hear? Cleopatra's? Napoleon Bonaparte's? George Washington's, Thomas Jefferson's, or Benjamin Franklin's? Doc Holliday's?

Imagine your world without movie sound-tracks, records, CD’s, tapes, iPods, YouTube, country or rock stations, or any other kind of music stations on the radio. To hear a Beethoven symphony, you’d probably have to live in or visit an urban area and pay to hear an orchestra play it.

That was the world before Thomas Edison invented the technology to record and play sound.

Now imagine you’re Frank Sinatra living and singing in 1905 (OK, OK, he wasn’t even born until 1915, but you get the idea) and you want to sell 200 copies of “New York, New York”. Because wax cylinder records could only be recorded one at a time, the best you could do was set up 10 machines at a time, and sing the same darn song over and over.

That was the world before Emile Berliner devised a way to make master recordings for pressing multiple discs.

The legendary jams of Jimi Hendrix, Pink Floyd and Iron Butterfly couldn’t possibly be recorded on the vintage wax cylinders that were limited to no more than two minutes. Today, technology has moved us beyond a 40–minute LP to electronic recordings with virtually no limits.

Bottom line: we take recordings for granted nowadays, but that wasn’t always so.

Beginning as a collaborative endeavor between inventors, the Talking Machine industry became like the Wild West, with outrageous advertising, furious fights over product names, innumerable lawsuits about patent infringement, and seemingly endless litigation between and against the major players in the business of recorded sound.

Edison envisioned his talking machine as a product for business dictation, but the invention didn’t catch on with the public until it was marketed as entertainment. As the technology leaped forward, discs overtook cylinder records, and internal horns replaced external horns, quality of sound wasn’t necessarily the deciding factor for market success. Edison’s Diamond Disc Phonograph supposedly produced the clearest tone of any machine, but it had limited sales.

Take a look and have a listen to the collection of talking machines at the Stagecoach Inn Museum. It’s a treasure trove of stories about cutting-edge mechanical technology, beautiful industrial design, and the clash of creative personalities.

And keep in mind what a quiet world it would be without recorded sound!

Before you start exploring the collection, you'll need to know the following terms:

ACOUSTICAL RECORDING

“Before the adoption of the microphone for recording in 1924, all records were made 'acoustically', that is to say by purely physical means with the sound waves 'taken' directly from vibrations in the air channeled down a recording horn to a recording 'cutting' stylus moving over a receptive revolving surface [such as a wax-coated cylinder. Unlike modern recording sessions,] It was impossible to modify or combine these recordings once taken, meaning that every recording is a true reflection of everything performed in the minutes between the session beginning and ending” [Gramophones and Phonographs Web site, Howard Hope].

When recording, a singer had to practically put his or her face in the recording horn. Depending on the type of instrument and where it was positioned, it might or might not be heard on the recording. Bands often favored louder instruments such as trumpets, cornets and trombones.

TALKING MACHINE

A machine that reproduces sound by means of a stylus (needle) vibrating in a grooved cylinder or disc. The sound of the vibrating stylus is amplified acoustically. Talking machines included Phonographs, Gramophones and Graphophones, to name a few brands. The brand names were the protected property of various companies and use of somebody else’s name often resulted in a lawsuit.

“The trade settled for the term 'Talking Machine' as a legally safe and understandable catch-all term for all the different players available. The term soon became archaic as the public were happy to settle for the words gramophone and phonograph and the major companies admitted defeat in the face of popular usage before the First World War and ceased litigation” [Gramophones and Phonographs Web site, Howard Hope].

Because the early machines recorded as well as reproduced sound, they were originally marketed to the business world for dictation. Stenographers weren’t happy about this, and the idea fizzled. People did record personal messages on cylinders, and, provided the party one sent it to had the correct machine, it was a way to communicate verbally with friends and loved ones who were far away. Eventually, enterprising folks began taking talking machines on the road to play them for the public (usually for a fee), and coin-operated machines found their way into public spaces. It wasn’t long before talking machines were designed and marketed for home use.

PHONOGRAPH

The brand name of Thomas A. Edison, Inc.’s (Thomas Edison’s) talking machines.

GRAPHOPHONE

The brand name of Columbia Graphophone Company’s (Alexander Graham Bell’s) talking machines. The Graphophone was aimed at the home entertainment market.

GRAMOPHONE

The brand name of Victor Talking Machine Company’s (Emile Berliner’s) talking machines. Gramophones did not play cylinder records, only discs. While Phonographs and Graphophones could also record sound, Gramophones could not.

HORN

Early machines came with listening tubes rather than horns. Horns were often sold as optional accessories. Early horns were conical, evolving to elaborate petal shapes. They were made of wood, brass, aluminum, glass, even papier mache’. After-market companies also manufactured horns and other equipment.

In general, a larger horn made a record sound better. As horns became bigger, they were supported by a floor crane or a self-supporting crane balanced by a foot that clipped under the front of the case. Often quite beautiful, horns still took up a large amount of space in a crowded parlor, prompting design of the “interior horn”.

“When the steel needle…or jewel stylus…glides over grooves of a disc or cylinder record, the needle/stylus is vibrated. The needle/stylus is attached to a diaphragm – much like the head of a drum. The diaphragm, now vibrating in sympathy with the needle/stylus, produces sound. But at this point the sound is thin and “tinny.” If the sound waves are allowed to travel into a horn (sometimes through a hollow tone arm; other times directly into the horn), the sound is directed and allowed to expand its frequency range – especially in the lower end – and also in volume (think of a cheerleader’s megaphone) [Antique Phonograph Society Web site].

VICTROLA, AMBEROLA, GRAFONOLA

The suffix “ola” indicated that the machine had an interior horn (hidden inside the cabinet, instead of protruding into the parlor where someone could bump into it). Sound came out through louvered doors (a.k.a. tone control leaves), which also provided some volume control. The Victrola was made by Victor, the Amberola by Edison, the Grafonola by Columbia. In 1906, the first internal horn machines became widely available, and by 1912 these were outselling the external horn models.

TINFOIL – (Nope, not used to cover the casserole dish.)

“Edison’s original invention was a drum covered in tinfoil that moved linearly past a fixed soundbox equipped with a blunt needle which embossed the tinfoil as it passed beneath it. Tinfoil phonographs were purely scientific instruments capable of demonstrating the principle of sound recording but the machine only became viable as an entertainment medium when cylindrical wax records were substituted for the tinfoil in the late 1880s” [Gramophones and Phonographs Web site, Howard Hope].

CYLINDER RECORD

What we usually call “wax cylinders” were actually known as records, or cylinder records, designed to be played on cylinder machines. Compared to discs, they had the advantage of being able to make home recordings, as well as better sound quality. Grooves in the records were cut vertically, or “hill-and-dale”, versus the lateral method used for discs. Cylinder records were made of wax compounds, easily broken and easily worn out. They could not be mass-produced. Singers were reluctant to join recording sessions that, at best, consisted of a bank of 10 machines each recording one record at a time. Cylinders were difficult to store and the date and title of a selection and name of the performer could not be inscribed on them, so printed paper slips (easily lost) were inserted in the cylinder storage box. Often this information was recorded at the beginning of a performance.

1912 Edison Hand Shaving Machine

RECORD SHAVER

An attachment or separate machine that shaved a thin layer of wax off a cylinder, enabling re-use of the cylinder, often multiple times.

DISC

“While most experts declared Edison's cylinder record to be superior sounding to any disc, the cylinders were expensive to manufacture, fragile, and bulky. It was the ease of storing discs more than anything else that propelled discs to the top of the sales charts. The superior marketing of the disc players and greater abundance of music available on discs was also a huge advantage. By 1905-1910, disc sales far outpaced cylinder sales”[Mulholland Press Web site; Robert Baumbach; 2014].

Emile Berliner, after years of experimenting with the best way to etch grooves into a flat disc surface, was producing disc machines by 1895. The first professional disc recording studio was opened in Philadelphia in 1897. Discs could be easily mass-produced, a relief to musicians who had to perform the same number over and over to produce enough cylinder records to sell to the public.

2- AND 4-MINUTE RECORDINGS

“When 10 and 12-inch disc records were placed on the market, the extra playing time gave them a distinct advantage over the cylinders which only played for about two minutes. Edison was to counter this by producing in 1908 a new cylinder record called the Amberol record which played for four minutes. This he achieved by using finer grooves rather than larger records ["Care and Conservation of Talking machines" by Richard Rennie; Papyrus Books; 1984].

Some cylinder machines were able to play both a 2-minute and a 4-minute recording.

SPRING MOTOR

The spring motor is wound by a hand crank or a key, much like you would wind a watch or music box. The Edison Spring Motor Phonograph appeared in 1895. Earlier products had a foot treadle, or a hand crank that needed to be turned by hand for as long as the cylinder played. Later products had more than one spring to turn the cylinder or disc, and would play multiple records with a single winding.

MANDREL

The tapered drum that holds the cylinder record while it plays.

TONE ARM

A movable hollow tube which conducts sound to the horn from the soundbox.

STYLUS/NEEDLE

A cylinder machine uses a jewel (diamond or sapphire) stylus, disc machines use a steel needle. The stylus or needle is attached to the flexible, circular diaphragm, which lives in the reproducer or sound box. It is the vibrations of the stylus or needle in the grooves of the cylinder or disc that vibrates the diaphragm, producing sound.

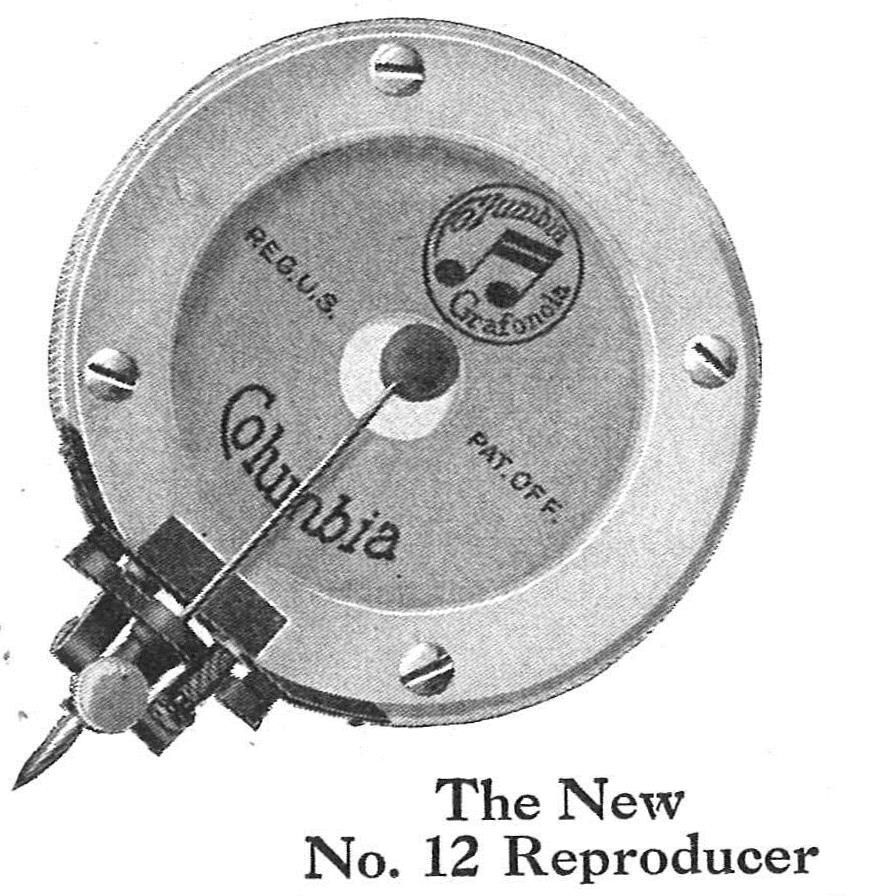

REPRODUCER/SOUND BOX

The component comprising a stylus or needle, linkage, and diaphragm, which reproduces the sound from the record groove. Edison used the term “reproducer” and Victor called it a “sound box.

NIPPER THE DOG

Nipper (1884-1895) was the model for the painting “His Master’s Voice”, painted by Francis Barraud, which became the Victor logo. He was named Nipper because of his penchant for biting the backs of visitors’ legs.

“According to contemporary Gramophone Company publicity material, the dog, a terrier named Nipper, had originally belonged to Barraud's brother Mark. When Mark Barraud died, Francis inherited Nipper, along with a cylinder phonograph and a number of recordings of Mark's voice. Francis noted the peculiar interest that the dog took in the recorded voice of his late master emanating from the horn, and conceived the idea of committing the scene to canvas” [Wikipedia “His Master’s Voice”].

PIONEERS IN SOUND

Although many other companies and personalities eventually entered the talking machine business, especially after patents expired, in the United States there were three main manufacturers in the business: Victor, Columbia, and Edison.

Thomas Alva Edison

After the novelty of Thomas Edison’s first talking machines wore off, the phonograph languished. Edison envisioned it for business use, not entertainment.

Alexander Graham Bell

When Alexander Graham Bell and his associates began experimenting with ways to improve on Edison’s invention and market to the public, the stakes went way up and the patent wars began.

Emile Berliner

When Emile Berliner began developing his disc-playing Gramophones, the competition became fierce and companies were formed, went bankrupt, evolved, changed hands, engaged in industrial espionage…you name it. Market share, price, product quality, recording contracts – all were on the recorded sound battlefield.

© 2019 Kathleen E. Boone